The BioSphere|DataSphere project acknowledges the deep, longstanding and ongoing connection of the Palawa and Pakana people to the wild, beautiful coast and sea country where the Tasman Fracture Marine Park is situated.

Between 2021 and 2024 artist Nigel Helyer worked with an interdisciplinary and multi-agency, team of scientists researching the environmental productivity of the Tasman Fracture Marine Park, a 43,000 square-kilometre marine reserve extending from the southern coast of Tasmania.

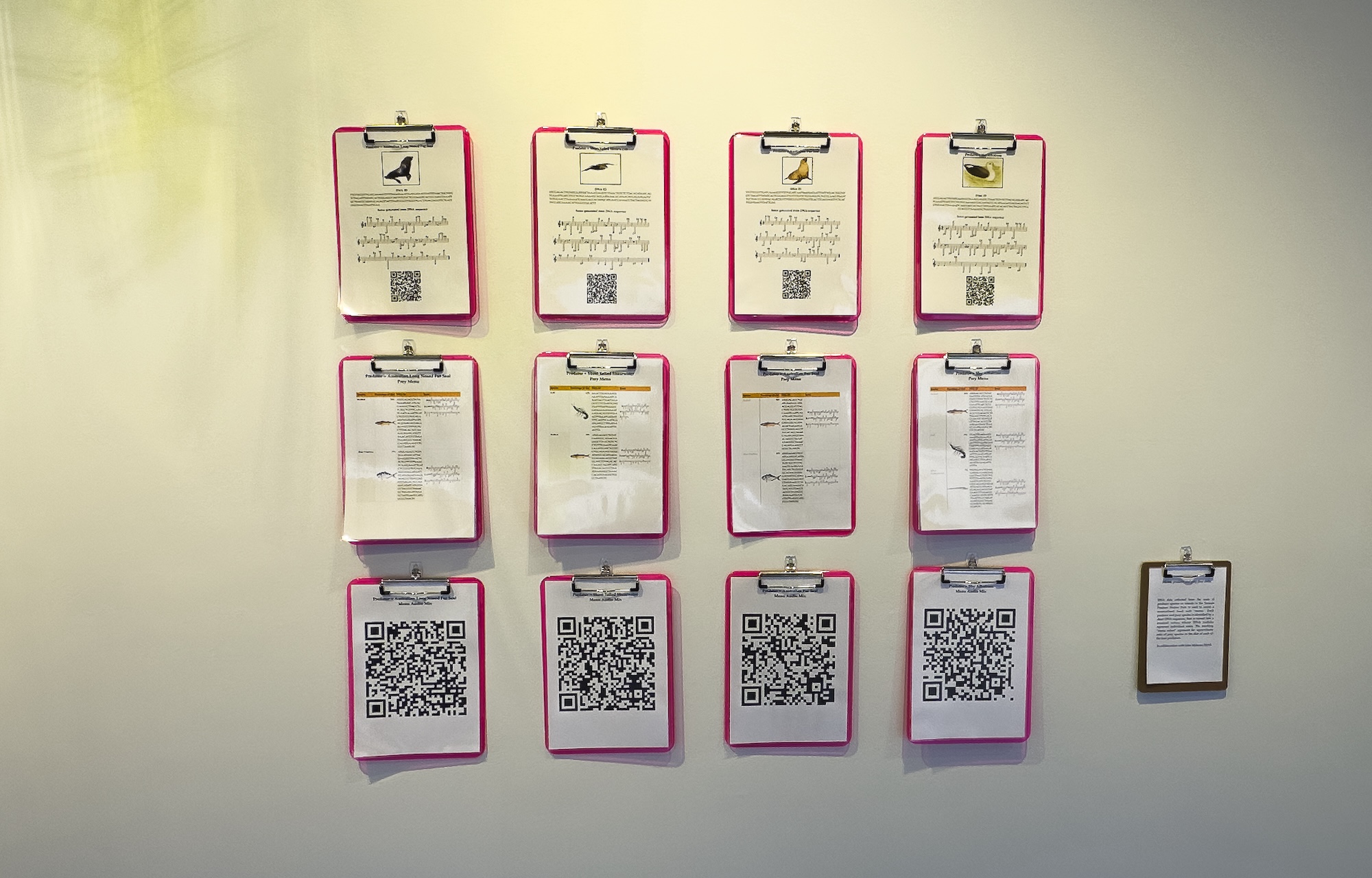

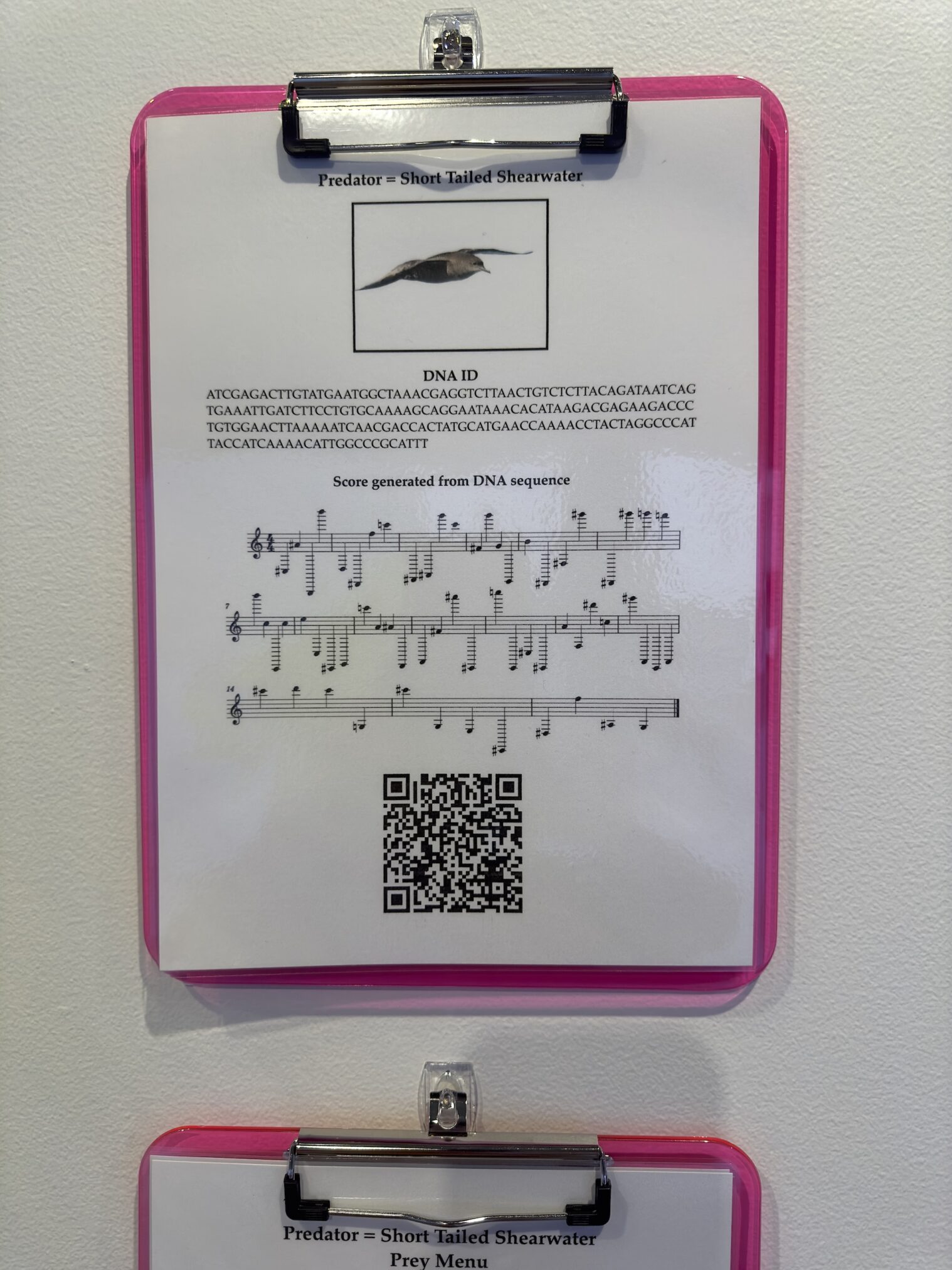

The BioSphere|DataSphere exhibition presents a series of creative interpretations of the wide range of scientific data generated by field research. Audio data collected by a submerged monitoring buoy is transformed into sculptural forms and animations that reveal diurnal fish choruses. Sea surface temperature data, sourced from decades of satellite imaging, is converted to create an animated musical sound map of Tasmanian waters. DNA sequences extracted from the scats of marine predators, collected on remote islands are used to generate musical scores that sonify the complex prey and predator food webs — and a photo montage presents the artist’s reflections on a field trip to the remote Maatsuyker Island to tag and monitor migratory yula/Short-tailed Shearwaters.

L’art c’est la science faite chair’. Jean Cocteau, 1918.

Art is science embodied, encapsulates a concept of art and science as two expressions, as two voices of the same spirit of enquiry, but perhaps delivered in a different register. Cocteau’s phrase employs the French word chair, in English quite literally flesh, emphasising that art brings science into the visceral realm, as a palpable experience, making it something that all can relate to — a narrative behind the data!

It is this embodiment of curiosity, knowledge, and sheer wonder that the melding of art and science is all about. The oceans are front and centre of the climate emergency the most crucial matter for the future concerns of artists and scientists alike.

BioSphere|DataSphere four collaborative projects:

Heat.

Working in collaboration with Chris Chapman of CSIRO we developed a heat map of the waters around Tasmania based on decades of satellite imaging. Calculations of the sea surface temperature at the depth contours of 200m, 500m, 1,000m, 2,000m and 3,000m were assigned to musical pitch and transformed into monophonic scores. An instrument then played each depth contour score and the five layers were mixed into a soundtrack that accompanied a visualisation (of the same data).

The same data was rendered as a series of Radar graphs.

ReSound

ReSound is a response to a massive data set of underwater audio collected by a buoy moored in the Tasman Fracture. The data was divided into twelve one-week periods and developed into two series of sculptural data clocks. The first series was formed from 2D laser-cut profiles and the second as 3D prints in nylon and ceramic. Several of the resulting forms were also animated as a data projection.

Each form can be read as a 24-hour clock, with the vertical axis representing audio frequency and the horizontal axis representing amplitude. What became strikingly evident are the bulges or horns that protrude from the data forms, arrayed at approximately 180 degrees. These correspond to the underwater dawn and dusk fish chorus. ReSound was undertaken in collaboration with Brian Miller of the Australian Antarctic Division.

Menu

Working with Julie McInnes of IMAS I was able to access the DNA data that her team used to identify four principal marine predator species – Short Tailed Shearwaters; Shy Albatross, Long-nosed fur seals and Australian Fur Seals. The team collected the scats of these predators at various remote island sites, over a range of seasons, which allowed them to identify the various species comprising their diet by DNA analysis.

My (lighthearted) approach has been to convert the short DNA sequences of both predator and prey into musical notation, and hence into short compositions, where each DNA I.D. is assigned to a different instrument. This material is then displayed graphically like the clipboard menus used by cafes and bistros.

Images of the species sit alongside their DNA identities and corresponding short musical compositions, which are accessed via QR codes.

Maatsuyker.

Each evening the sky is filled with the calls and the slicing scimitar wings of thousands of yula (Short-Tailed Shearwaters) returning to roost. Once on the ground, the birds have an extended range of vocalisations which I am recording. In the pitch black, under a tight canopy of Melaleuca, the night becomes a surreal soundscape. 04h00 — It is cold in the pre-dawn, the ground is damp and looming above the mountain, pulses with the calls of 800,000 birds. Before first light, a torrent of dark forms bursts from the narrow track into the grassy clearing — the birds so graceful in the air, but so awkward on the ground, scramble into flight with a rapid surge of wing beats to narrowly clear the tree canopy away into the updraft of the sheer cliffs. Shearwaters are named for what they do best, the graceful and almost incomprehensible skimming of the ocean waves — an effortless flight with barely a wingbeat. A few stragglers get airborne and finally, the mountain is quiet, the first rays of sunlight illuminate the horizon — the next shift takes over — the dawn chorus. The Maatsuyker project was undertaken with Mary-Anne Lea of the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies.

Listen to an interview conducted by Robin Petterd.

Check out his podcast series (Creating New Spaces).

Acknowledgements.

Many thanks to the scientific partners of each of these works: Brian Miller (Australian Antarctic Division); Chris Chapman (CSIRO); Julie McInnes (IMAS/AAD); Sam Thalmann (DNRET); Sheryl Hamilton (DNRET/Friends of Maatsuyker Island); and Mary-Anne Lea (IMAS) — and to Svenja Kratz, Murray Antill, Peter Maarseveen (University of Tasmania School of Creative Arts and Media) and Jane Barlow from The Plimsoll Gallery for their support. Lastly, I thank my wife Cecelia Cmielewski for her encouragement and support. This project was made possible through funding support from the Australian Government’s Our Marine Parks Grants program.