Exhibited.

Arizona State University 2002.

Biennale of Electronic Arts Perth 2002.

Stanford University Gallery 2003.

Boutwell Draper Gallery, Sydney 2003.

Materials.

Timber, Carpet and Prayer Mats, Facsimile Landmine and Mine detectors, Audio electronics x16 channel, projection.

Dimensions.

19m x 10m x 4m.

Notes.

In English, we speak of mines sown in fields or laid somewhat akin to an egg, or perhaps a cunningly laid trap. This is a domestic and agricultural lexicon whose familiar words belie the barbarous intent of these small kernels of violence.

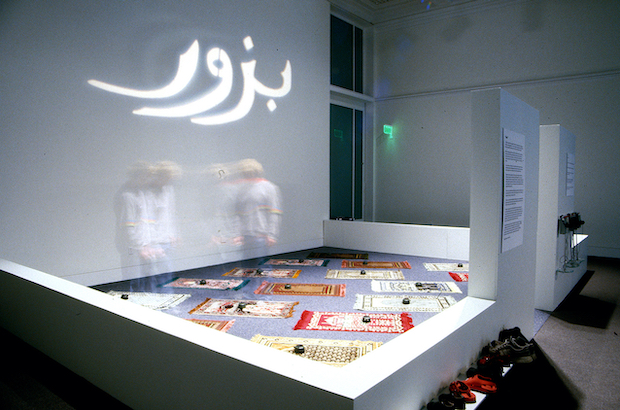

Seed at the Biennale of Electronic Arts Perth, Curtin Gallery.

Mines are ontological devices; they lie in wait for the future! Such a concept is resonant with the Old Testament parable of the sowing of seed, in which the germs of the future are broadcast, as if by chance, across a varied range of terrain, some fertile and fruitful, and some stony and barren, in an ecology of destiny. In a more obvious combination of the fruitful and the fatal, we might recall the recent aerial seeding of Afghanistan with small yellow packages, some round and some square, some containing food but others deadly ordinance.

Facsimile Russian landmine with Prayer-mat.

Whilst the physical geography of Islam acts as the historical context for the mythopoetic spaces and narratives of the Old Testament it acts as a repository for hundreds of thousands of landmines – a testament to the failure of military solutions to generations of economic and political instability. Should we heed the adage “As you sow, so shall you reap” then an optimistic future in the region is less than assured.

Interacting with the sonic minesweepers.

“Seed” is a sonic installation that metaphorically collides our agricultural lexicon of the minefield with the narratives of the Old Testament and the contemporary disasters of military and ideological conflict.

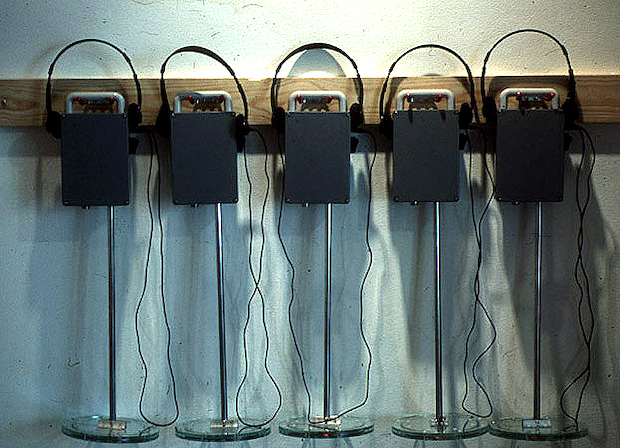

Sonic minesweepers.

It does so by inviting the viewer/auditor to enter a sonic minefield. Each visitor may equip themselves with a simple mine detector that will allow them to listen in to the sonic terrain emitted by the mines.

Perhaps to their surprise, the small facsimile landmines, each resting at the centre of an Islamic prayer mat, do not voice strident political commentary, the sounds of battle or doctored media grabs! Instead, the encounter is with a sonic world of looped Arabic music, some ancient and some contemporary, overlaid with voices, in Arabic and English, which enunciate the ninety-nine names of Allah, each name supported by a brief extract from the Koran.

“Seed” therefore proposes a place of complexity and ambiguity within which to contemplate the simplistic and unilateral position of current military and political events. It is after all sobering to consider that the death toll inflicted by landmines (principally in the developing world) is equivalent to the appalling destruction of the World Trade Centre – repeated five times each year. © Dr Nigel Helyer, 2002.

Listen to the seed mix ~ it gives a general idea of the 16-channel project.

Read an article by Joanna Mendelssohn; Artlink Issue 23:4

In the 1970s, when Gough Whitlam was Prime Minister of Australia, he once used the phrase ‘outer Baluchistan’ to indicate an obscure place where nothing much happened. Since then we have learnt that there is no place too obscure to claim its fifteen minutes of fame, and Baluchistan has been more crucial in the affairs of the world than our oversize island that straddles the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Seed, Nigel Helyer’s sound piece on the impact of the terrible mechanisms of war on once-obscure Islamic states, crosses a most difficult cultural divide. He brings together the precepts of the shared Old Testament ancestry of Islam, Jewish and Christian faiths. Through his art, he shows both an appreciation for their teachings and an awareness of how far those who chant the slogans have strayed from the principles of the faith. Seed is a work about futures and landmines that are sown by foreign powers in distant lands to be reaped by children playing, perhaps years later. It is a reminder of the Biblical culture of sowing and reaping – and there is a terrible dividend in the harvest. Most importantly, Seed brings these ancient concepts into the devastating present, the age of electronically negotiated war.

At the entrance of Seed is a display of worn children’s shoes, apparently discarded at the entrance of a place of prayer (it was the children of Afghanistan who chased after the yellow packages that looked as though they contained food – then they exploded on contact). Behind the wall is a colourful display of prayer mats, of the kind of cheap and colourful cloth found in any Pakistan or Afghan market; and on each mat, a small facsimile landmine.

Helyer is, of course, a sound artist. And it is sound that gives these works their impact. The viewer enters the space with ‘mine detecting’ tools and headphones. As each mat is approached it does not explode. Instead, the ‘mine’ is revealed to be a sound unit that beams its message to the ‘mine detector’. In the ‘minefield’ the listener hears words and music from the Islamic culture of otherness which our political leaders tell us is a part of the Axis of Evil. And what do we hear from these voices at prayer and play? The first sounds are of music, both sacred and secular, from Afghanistan. Then there are the voices. Some of these are inaudible, but they include the ninety-nine names of Allah and different ways of describing the greatness of God.

‘Our Lord will bring us together and he will judge us with the truth’ says a voice in English. ‘Creator. Know thy Lord and he is the all-wise creator’ intones another.

Helyer’s work therefore carries a message of the contradictions of war and prayer, as he reveals that the religion denounced as part of ‘The Axis of Evil’ is one which upholds the same values as the persecuting Christians and Jews of the United States and its allies. The terrible events of recent years have led to new directions in political art as the world seeks to find some meaning in the tragedies of our time. With Seed Helyer has created a work that works as a visual/sensual experience while making even the most hardened warmonger think of the empty shoes of the children of Afghanistan, and how the children lost their legs.