Exhibited.

Metronom Gallery Barcelona 2003.

Auditori CAM, Alicante, 2003.

Stanford University Gallery 2003.

Ars Electronica 2007.

The Science Gallery, Trinity College Dublin 2011.

Materials.

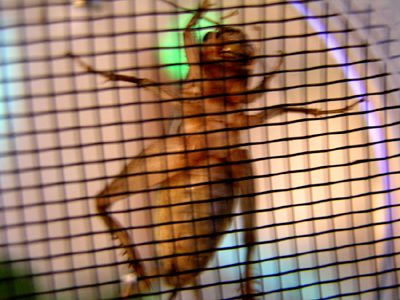

X2 DVD projections, x100 Insect cages, x25 Laboratory stands, x200 Crickets.

Dimensions.

Footprint variable, individual units 2m x 2m x 2m.

Notes.

Host is an installation developed at the ‘SymbioticA’ Bio-Art and Technology Laboratory (University of Western Australia) in which an audience of live Crickets attend a lecture concerning the sex life of insects.This page has the original documentation but please also see the final incarnation of of Host exhibited at the Science Gallery, Trinity College, Dublin, Eire.

The lecture, in the form of two DVD projections, has one sound track recorded directly from the speakers voice, whilst the other was recorded via the aural nerve of a Cricket. If nothing else, this installation is ample proof that our own sex lives are much less interesting than we suppose!!!

Anyhow here is how it all happened!

The old Professor and I are scrambling about in the bush armed with ultra-sonic bat detectors, only we are using them to track down crickets. The bat detectors down-sample high frequencies into the audible range but the Prof is slightly alarmed that I can hear the critters without the aid of the detector, mark one up for “Golden Ears” I guess!

The two senior scientists tell me this is a piece of cake, in fact it was a standard lab demonstration before students got all PC and squeamish, so they are a little out of practice! It turns out to be a messy operation affixing a live ‘subject’ to the experimental stand with hot wax, the cricket is uncooperative, the scientists swear like troopers but persevere. Insects they tell me fall outside of ethics requirements as they have no feelings (do they mean souls I wonder?).

Crickets hear through their elbows the sound traveling inside the upper forelimb to a membrane that excites nerves connected to the aural nerve centre in the thorax. This is where the first micro electrode is inserted, the circuit being completed by another in the abdomen; the cricket is hooked up to an oscilloscope and is thus transformed into a microphone!

On comes the lecture, a racy monologue concerning the exotic sexual practices of insects, hard-core fetish pales into insignificance compared with these antics. The oscilloscope flashes and pulses as the cricket’s aural nerves fire, re-set and fire again. In the lab we settle back to drink tea and listen along with our insect friend who performs diligently for four hours before expiring. At this juncture I feel more than just a twinge of remorse for this small death, notwithstanding the fact that we daily execute insects by the million (I rationalise) entire industries serve this single exterminating purpose, ensuring our hygiene and our food security.

I console myself that Host is something of an insect liberation project, as the 200 ~ 300 members of the live cricket audience are saved from certain doom (they are purchased from pet stores, where their destiny is to be eaten by pet amphibians and reptiles). After serving as a (captive) audience for a week, by which time they will have listened to the sex lecture some 150 times, the crickets are released and a fresh cohort installed. I only hope that in the brief time they have left they can do something useful with all that knowledge!

Like a hapless insect embroidered into the corner of a spiders web I am reversed into the corner of the tiny market stall and positioned on a small yellow plastic stool. The dealers have me where they want me, a fine exotic catch, I can only escape through negotiating the best deal possible even though I will pay through the nose! We sit smiling and sweating in the Shanghai summer, talking numbers, poking calculators and smiling again – all around a cacophony of cricket stridulations. Men are obsessively filling miniature ming dishes with cricket sized portions of gruel, transferring prized Katydids from earthenware jars to fancy carved wooden cages, or cocking an ear to a song.

Face saved all round and I walk away with some exquisitely fret-worked pocket cricket cages, a small organic transistor radio really, content in the knowledge that in China crickets have a soul!

Exhibition Notes.

The Host installation has been re-mounted in three new versions, at Ars Electronica as part of the Symbiotica group exhibition, celebrating the award of the Golden Nica for the work of the Lab simultaneously version 03 was on exhibition in Mexico City as part of the exciting Transitio_MX02 New Media Arts Exhibition and Symposium. The project is included in Visceral, the Living Art Experiment at the Science Gallery Trinity College Dublin, Eire in 2011.

For more information go to the Ars Electronica website.

For more information go to the Transitio_MX02 website.

Be not afeared; this isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears; and sometimes voices

That, if I then had waked after long sleep,

Will make me sleep again; and then, in dreaming,

The clouds methought would open and show riches

Ready to drop upon me, that, when I waked,

I cried to dream again.

Caliban in Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

Natural sound-scapes that we perceive as intricate and seamless natural compositions; a forest at dawn or the metropolis at rush hour are in reality conglomerations of independent and unrelated sounds. What appears to the auditor as a structured and syncopated whole, arises from a vast array of largely unrelated sonic events, some intentional, many accidental. All are spatially displaced but all converge upon our ears which form the centre of the soniferous universe in which we are immersed.

In effect our senses form a Procrustes Bed upon which the palpable world is forced to comply. Therefore that which we naturally assume to be comprehensive and exhaustive is simply a small portion of a vast spectrum that extends well beyond our perceptual horizon.

The Host project suggests that for a moment we abandon our Anthropomorphic worldview and think about life (well actually think about sex) from the perspective of an insect. We are invited to join an audience of Crickets, who are attending a very serious scientific lecture on the sex life of insects, which we quickly realise is rather more complex and interesting than our own!

One screen shows the heavily pixelated talking-head of the scientist, the other an image of an oscilloscope signal. The oscilloscope image with its crackling sound-track was obtained under laboratory conditions and is a direct recording of the electrical activity in the aural nerve centre of a Cricket which is listening to the sex lecture. From one perspective the creature becomes a type of electro-physiological microphone – but at a deeper metaphorical level we are asked to re-consider our own perceptual assumptions about the world.

Nigel Helyer, Ars Electronica Linz 2007.

Read the Sex lecture Transcript below: –

I’m going to talk about the reproductive behaviour of insects. Insects are a huge diverse group and of course as they are probably the first terrestrial animals they have been around very long time, so they have been evolving for much longer than vertebrates and they are a much more diverse, particularly because of their exoskeletons, they can make themselves into practically any shape they want. But their mating behaviours are very much diverse and complex than vertebrates. Of course, the big pressure for developing strange sexual behaviour … it is dimorphism, the change and shape between male and female insects. Any animal where the male doesn’t really have a role to play in looking after the young means that the males are free to evolve in different ways than the females. In general, what happens is that you have less investment in looking after the young so the males can evolve mechanisms that enable them to succeed in their reproductive behaviour.

When you have lots of male insects competing for one female, which happens when males are smaller and have less nutritional requirements than the females, then you get intense competition.

One of the different things about insects is that a lot of what is known as cryptic-selection by the female so the female insect can actually determine whether the male mates, and not necessarily like in vertebrates, before they actually mate.

It’s interesting that most insects actually continue their courtship behaviour after intercourse, so after coitus has happened the male would still stimulate the female make a song, flap its wings, bump its head, whatever the particular mating behaviour it is. Now, when you think about, that’s very odd, in vertebrate terms. Why would you continue to try and seduce the female after you’ve already seduced the female? Well, the reason for it appears to be that in insects, because the sperm are not deposited directly on the eggs in most cases, but it may be held in the female, in a special chamber called a spermatheca. The female has a real say in whether she is going to use that sperm or not. And there’s lot of evidence from many different studies showing that the female may make choices on what to do with that sperm depending on the nature of the male, so if the male is small, if it didn’t stimulate the female well, or if its song was weak. Various things which indicated to the female that the male was not the best male she could have. But the female has various ways of stopping that male sperm from fertilizing the egg. Everything from a special valve that cuts off the transport of sperm from its storage area to the egg, to actual reaching in and pulling the sperm out, to producing fewer or no eggs after the mating, to using less of the sperm and therefore reducing the chance that the male will fertilize the egg.

Therefore, there are many different techniques that the female can use to stop a sub standard male fertilizing her eggs. So often, the male would do things after his mating to encourage the female.

In the crickets and Orthoptera in general, have perhaps more mechanisms to do this than many insects. In particular what they do is produce a special secretion called the Spermatophylax that they place over the sperm and this is a big gelatinous blob about half the size of the males abdomen, so this is a big investment for the male, and the female will often turn around and eat this mass so it might be thought that it is a nutritional mass, sort of the male actually investing in the offspring but that seems to be fairly rare. Only a few cricket species have demonstrated that if this is removed, the female lays fewer eggs or that the eggs are smaller. Therefore, it has a different function. So, what it seems to do in most cricket species is actually stop the female from removing the sperm so if you’re a big healthy male you deposit a great blob of this stuff on top of your sperm and then the female eats it but it stops her getting through to the sperm. It takes her a long time to eat this mass and stops her from getting through to the sperm and removing the sperm.

This is particularly useful if you are a small weedy little male, because another strange thing about insects is that they can be of all shorts of shapes and sizes, depending on the environment they were brought up in. Therefore, you might start with a small egg, have poor nutrition throughout your life and become a male adult but a very small.

This happens to some extent in humans but a lot about our sizes is genetically determined. But in insects you can have two males fully grown that might be in mass five or six times larger than a smaller one.

Therefore, the males often have a range of behaviour repertoires, which they bring out depending on their size. Therefore, if you were a little male then you would try to mate sneakily whilst two large males are fighting. Whereas is if you are a large male you will do everything to keep off the other males and perhaps flip off the little male if he’s trying to mate with the female.

This might be why you have the evolution of things like the Spermataphylax because if you’re a big male, you want to have some way of stopping or preventing the sneaky male from getting in there so, you deposit a big plug to stop the other male from getting in there.

The other thing is that the male has to persuade the female that he is a big, healthy, that she really wants his genes. One way of doing this is to deposit a big Spermatophylax but in the Orthoptera, they have also developed other ways of keeping the female amused or impressing the female while in mating. In particular, a number of the Orthoptera actually feed the female with her own body parts. So, some crickets have evolved their wings and special fleshy plates on their wings that are sort of sacrificed to the female. The female eats them but they’re actually designed for the female to eat. Moreover, the selection pressures have lead them to actually be more tasty or making them more fleshy so that they are attractive to the female. In some species they actually eat the legs of the male and again the male has evolved particularly large fleshy legs to produce a good meal for the female and the bigger the male, the more the female is occupied by eating this and presumably the more likely she is to allow the sperm through, to use the sperm from that particular male. In addition, some studies have shown that where the female mates with a cricket that is large or has a good song repertoire that she will lay more and larger eggs. Whereas as if you clip the wings of a cricket, or his legs to stop the noise and stop him from having a good song, although they may still mate, the female will produce less eggs or the eggs will be smaller. As if she’s controlling the amount of reproductive effort she puts into that particular male, depending on whether she thinks that male is worth it or not.

In some crickets, they have special glands on their back and they secrete a sort of food substance from those glands that the female cricket will eat during mating. Again, not clear whether this is really a nutritional investment in the eggs so much as an inducement for the female to allow that sperm through. It’s a difficult issue because the female can control the size of her eggs. It is difficult to separate whether she is producing small eggs because she does not like that particular male or she is producing small eggs because she did not get much nutrition from the glands or the Spermataphylax. But it’s generally thought in most cases that it’s the size of the male which determines the investment in the eggs, not how much nutrition that individual is getting from the Spermataphylax. Over all in insects, they have evolved very complex genitalia too, to ensure that they correct species mate then in fact in many insects you can determine the genetic relationship and their evolutionary history from the former form and shape of the genitalia. They often form a sort of lock and key pattern, and because of their exoskeleton, insects can have very accurate matching patterns between the genitalia.

And this is really not a subject to other selection process for survival and is fairly random in the same way that there’s no rule as to what shape a key should have or a lock. As long as they are unique, there is no pressure for it to be one shape or another; it provides a very good marker for genetic relationships. If you have two insects with very similar shaped genitalia is presumably because they are related or they have evolved from a close ancestor.

Whereas as if you look at something such as leg shape or eye shape there’s probably a lot of convergent pressure to develop legs in a particular shape which are perfect for a cricket. So the fact that two crickets have legs that are similar may be due to them living in similar environments, it has nothing to do with a similar evolutionary history, whereas the shape of the genitalia is under no real selection pressure to match the environment. Therefore, if two insects have similar shaped genitalia it is probably because they have evolved closely together.

Interestingly the development of the Spermatophalax appears to have occurred, even just in Orthoptera about eleven separate occasions. So, there is a case that’s the opposite. In that case, it is clear that there is a lot of selection pressure, and so the fact that a number of them have evolved it doesn’t mean that they’re very closely related, it’s just shows that it is something very useful in an animal, where the female tends to remove sperm, or not use the sperm. It is very useful if you develop a sort of plug used to cover up the sperm to prevent the female from mating with another male and to prevent the female herself from removing sperm when she has decided she does not like the sound of your song. This kind of competition can reach real extremes in cases where the chances of mating depend on you eliminating your rivals.

So insects show all sorts of ways of eliminating your rivals from the battle, from simple fights, a bit like deer locking antlers, this occurs in numerous horned beetles, but also in some kinds of wasps with big horns, that lock horns and fight each other and the strongest one wins.

Often the female watches the battle closely, so the female is identifying which is the strongest male and that is the one that she will allow to mate. Nevertheless, in some other insects like the fig wasps, for example, where there may be one female wasp inside a fig and often in the figs, the insect is locked in until the fig ripens. There’s a really close relationship between the two species, the fig won’t be fertilized unless the wasp was in there and the wasp needs to be there to feed on the seeds and the pulp of the fruit.

In a number of these fig wasp species the males are wingless, because they are born and lived within one fig, their whole life experience is within that one fig. And if there are ten males in that fig and one female may arrive or be born, there then the male that manages to kill the others is the one that is going to mate. And rather than just competing with the other males they have developed huge jaws and fight to dead so that only one will survive and mate.

This also illustrates another extreme thing that happens with insects. Because a lot of insects go through a larval Pupae and Imago stage… like a butterfly, where you’ve got a caterpillar, pupae and then the adult, they can really specialize the reproductive phase. So, in a number of insects the larval is really just a feeding tube and it does nothing but feed and eat, it is just one big long digestive tube with just not enough mobility to get to its next bit of food and perhaps defensive or camouflaging mechanisms to hide it while its feeding. You then have pupae, then you have a reproductive stage, and in many insects, that reproductive stage may only last for a few days. And during that period the adult may not even feed. A number of insect species do not have any mouthparts, they have a very limited digestive system, or they may feed on nectar or nothing at all.

In such species, the post Pupae Imago’s role is simply to find a mate and all the energies for a couple of days may be put into finding a mate. And you get competition in ways mentioned already for the attention of the female but you also get what is called Lekking behaviour. This is first identified in a number of bird species, and the definition of a Lek is a place where males compete, not for resources or for food, but for mating rights, so it has to occur where there isn’t enough food. Therefore, for Birds a Lek maybe set up on a suitable area of rock or bare ground. It is like an arena where the males gather and show off or compete. And females may gather to watch, it is a bit like a gladiators forum and the female watches the competition amongst the males and then presumably identifies the one they feel they want to mate with.

Now, it appears that this does happen in insects as well; it has only recently been identified. What happens in insects is that you’ll find an area, a Lek, where the male insects will gather, often flying in a swarm, and they’ll all display or they’ll compete with other males by fighting and females will arrive and the males will compete for her attention. And these areas are often above a sunny rock or above an open space of water, as often happens with dragonflies, and it’s an area where the males can fight but also where females can decide who they want to mate with, because it’s often the female that’s deciding in the end whose sperm they will accept. But in insects it’s a double proposition: the males compete or may force their way through other males but also the female may decide which male to mate with or even if they don’t have much choice in that, they may then influence what sperm gets through or which set of sperm is used.

Males have developed various ways of competing amongst themselves, but also of persuading the female to accept the sperm or to remove other’s male sperm. In a number of insects species the penis is an extremely complex organ and is able to actually fit in and remove sperm belonging to other males that may have mated with the female previously, so they literally have to scoop out the previous sperm before they put their own in. One of the extreme examples of this is that there is a species where the male stimulates the oviduct of the female so the female thinks it is laying an egg and averts the ovipositor along with the sperm that is in it, and then the female eats the sperm. So, the male is doing this to get rid of the previous sperm of anther male so it can place its own sperm in the female.

All of these mechanisms are actually… you might consider pretty wasteful. It is quite extraordinary how much time and effort goes into the mating rituals and to the competition, which could be diverted, into just the survival of the offspring. So it is clear that the ability to re-sort genes, which is all that sex is about, is an absolutely crucial thing to the species survival. Rather than diverting all their energies to bring up the offspring, which is quite an unusual thought really, that 50% of the species in most insects, their pure role is to ensure a re-sorting of the genes so only 50% of the energy of the whole species is devoted to survival. So, sexual selection is clearly an extremely important part of the evolution and this is probably because it can act very quickly.

Traditional evolution by selection of features may have to happen over thousands of generations, there’s a slight survival advantage of having longer legs or bright and colored wings increases the survival of a particular gene over time. But with sexual selection, you have a “chicken and egg” situation, what makes the male or the female change this selection, but once that is changed, you can get evolution happening over a few generations. If you have a gene that makes females select for blue beetles you can have only blue beetles being accepted as mates and within two or three generations all the beetles will be blue. So, sexual selection is extremely powerful and an extremely fast way for the species to respond to evolutionary changes, but will happen through selecting for those animals that select for the right mates and therefore have the most offspring because of that selection. And there’s still a lot of debate over the way the sexual selection operates, even though way back in the 19th century Darwin had identified that sexual selection does happen.

Written and spoken by Dr Stuart Bunt, Symbiotica.

© Dr Nigel Helyer 2007.