The Brain is wider than the Sky

For put them side by side

The one the other will contain

With ease and You, beside

The Brain is deeper than the sea

For hold them Blue to Blue

The one the other will absorb

As Sponges, Buckets do

The Brain is just the weight of God

For, Heft them, Pound for Pound

And they will differ, if they do

As Syllable from Sound.

Emily Dickinson, The Brain is wider than the Sky (1862).

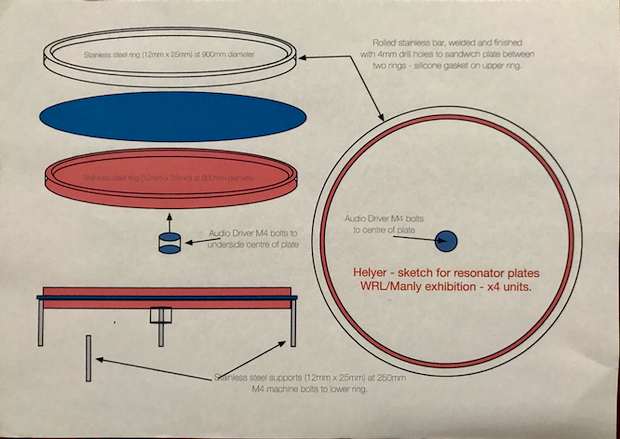

Four Chaldini plates, each driven by an acoustic actuator

rendering sonified wave height, tide height and sand movement data.

We are neurologically predisposed to seek patterns in our surroundings, in fact pattern

recognition is our core cognitive ability, vital to our evolution and survival as a species-

as it affords the capacity of prediction.

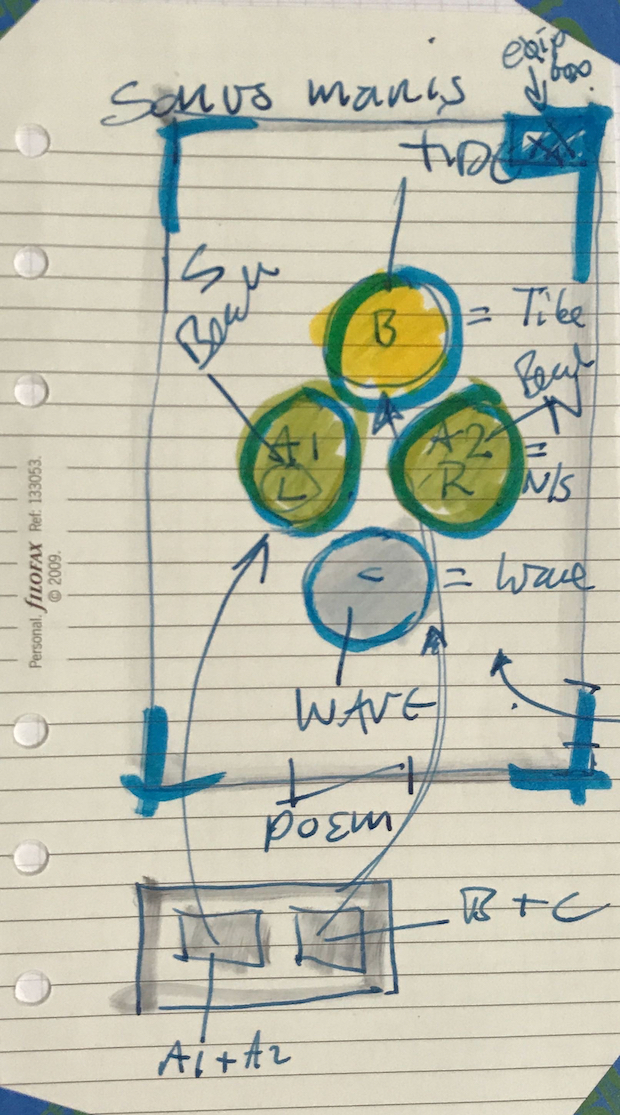

Sonus Maris installed at The Manly Gallery.

In life, as in art, we take delight in the symmetries, growth patterns and morphologies of

the natural world as through them we recognise our formation. However, there is

a constant flux between the regularity, or predictability of a pattern and an instability or

turbulence that might threaten to render it indecipherable — to walk this tightrope

between order and chaos is one of the central techniques of art, to distill clarity from

chaos is the purpose of science.

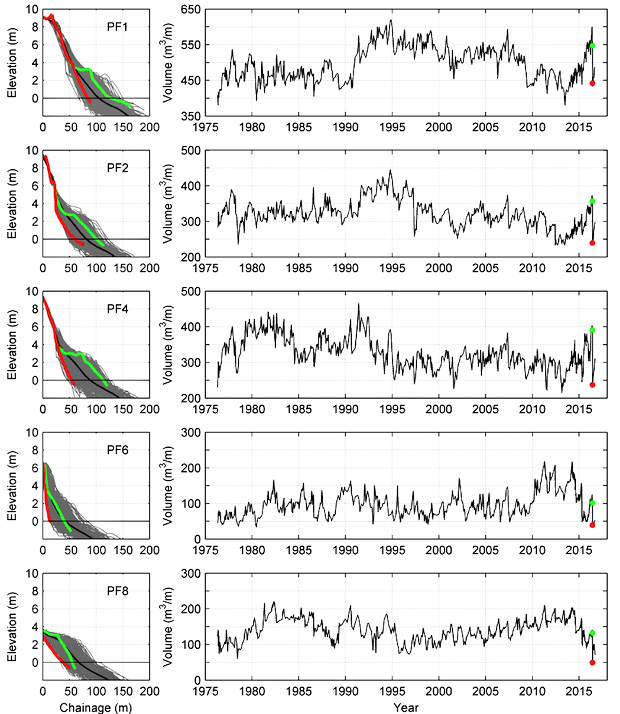

Sand deposition data.

In 1917 the Russian Formalist writer Viktor Shklovsky made a distinction between

poetry and prose, coining the term Ostranerie (or Defamiliarisation) a device for making

strange, to render a common thing in an unfamiliar manner or context to create a fresh

perception of it. This trope of making strange with language has recurred throughout the

twentieth century, surfacing as Freud’s notion of the Unheimliche (the uncanny) as

Berthold Brecht’s Verfremdungeffekt (the estrangement effect) and Jaques Derrida’s

Différance (which hovers somewhere between difference and deferment).

Narrabeen Beach, courtesy Chris Drummond WRL.

The probabilistic learning that pattern recognition develops is extremely useful in the

prosaic world — it is the way we navigate our daily lives. However, in creative practice, we

always require a twist to a narrative, a dissonant metaphor in a joke, or an unpredictable

note to conclude a melodic series. This is the sweet spot, the point at which our expectations of regularity in a pattern are disrupted — but not too much, just enough to throw the brain into mild confusion. It is the fissure, the reveal, and the punchline that reflect on the narrative arc and play with our assumptions.

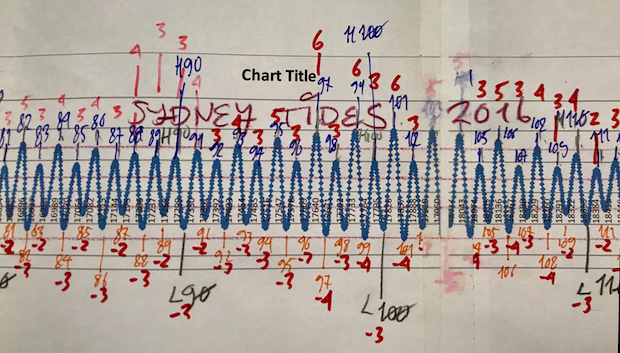

Quantising the Tidal data into a series of tones.

Science is based upon empirical evidence, it observes and carefully quantifies the

complex phenomena that surround us in an attempt to make sense of chaos. At the

small end of the scale, each wave that crashes onto the beach at Narrabeen creates

a turbulent swirl of sediment, multiplied thousands of times in each individual storm.

Construction drawing for the Chaldini Plates.

The Scientists of the Water Research Laboratory understand these individual events

as nonlinear interactions which are difficult, if not impossible to interpret or predict.

However, the lab has been monitoring the shifting shoreline at Narrabeen for over

43 years and from this long-term view it is possible to identify an accumulative effect

in which the sand volume rotates between the northern and southern end of the beach

in cycles that range between two to seven years.

The Layout.

When considered in conjunction with wave and storm data an overarching mechanism

driven by climate emerges — it is our point of view along the axis of the particular to the general that allows us to see the wood from the trees.

Artist Nigel Helyer with collaborating engineers Mitchell Harley and Chris Drummond

in front of “Sonus Maris (the sound of the sea)”. ”Manly Dam Project”, an exhibition

inspired by the unique landscape and cultural significance of the Manly Dam area.

Technical Notes.

Sonus Maris is the result of an Art and Science collaboration with the scientists and engineers of the Water Research Laboratory of the University of New South Wales.

The artist worked with data relating to the movement and deposition of sand on the beach at Narrabeen (in fact this is the world’s longest observation of sand deposition – taken over 43 years) and is accompanied by tidal data and wave height. The artist quantised these data and then assigned a range of tonal values, that are played via audio actuators fitted to four Chaldini plates* and which excite various particulate matter on the plate’s surface. Sonus Maris sonifies and visualises abstract data sets across the four plates and operates at very low frequencies generating a palpable and visceral experience.

The project has been extremely popular with both the general public and with the scientists and engineers of the laboratory – so we shall continue our collaborations.

* Ernst Chaldini (1756 – 1857 Hungarian/German) developed Robert Hook’s experiments of 1680 where he had observed nodal patterns manifest on vibrating glass plates (he employed flour activated by a violin bow stroking the edge of the glass). Chaldini patterns or figures are a method to demonstrate nodal boundaries in vibrating surfaces and have similarities with the solutions of the Schrödinger equation for one-electron atoms.

You will need to play this through audio actuators bolted to something big – or find some large sub-woofers 🙂

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.