Quelle est votre plus grand ambition dans la vie?

Devenire immortel et puis mourir.

Jean-Luc Godard, À bout de souffle 1960.

Fictionalising fiction.

As a thirteen-year-old lad, I along with a couple of friends, were once left to kick our heels for the day in central London —we were the crew in a sailing regatta waiting for our (adult) helmsman to finish work. Being both wary of getting lost in the capital and having little or no money, we decided to visit the cartoon cinema, which in those days was located on the main concourse of Victoria station. However, unlike each Saturday morning, our encounter was not as we had imagined, with Bugs Bunny or the Invisible Man but with something indescribable and utterly alien. I left the cinema with mixed emotions, no longer innocent, for I had seen my first film by Jean-Luc Godard and my experience of cinema had been irrevocably changed!

Freeze Frame; Cinema and the Afterlife, is a unique inter-disciplinary exhibition that explores, in sound and sculpture, the historical relationship between cinema and concepts of the afterlife, which emerged simultaneously with the earliest developments of the moving image, and theatrical forms of visual illusion.

The era of proto-cinema coincided with a range of inventors, such as Edison (and their emergent electrical technologies) who were philosophically open to the ideas of spiritualism, parapsychology and the means to communicate across the aether with both the living and the dead. Early cinema introduced methods that visually displayed the passage of time and the possibility of distorting or reversing the normal course and causality of events.

Speculative Fictions.

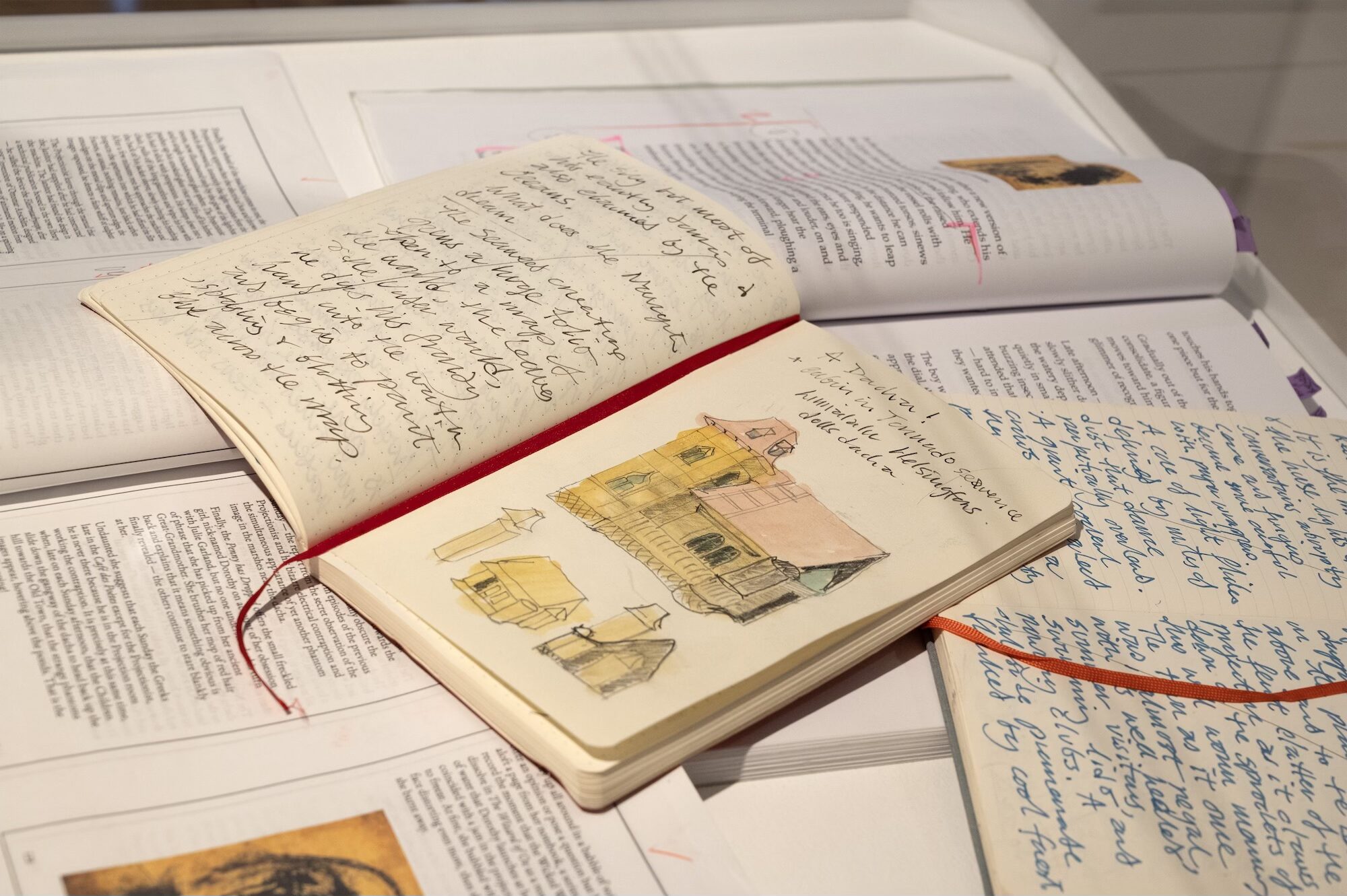

I have recently been conducting experiments which transform my normal studio practice and creative methods. As an Artist I have always looked for inspiration in literature; recently I have been challenging my normal creative practice by driving my studio work from the springboard of my own creative writing.

Freeze Frame; Cinema and the Afterlife, is an exhibition based on a novel that explores the relationship between our experiences of Cinema, and various mythologies of the Afterlife. The mise-en-scène – set in a ‘soft’ post-environmental apocalypse the narrative features a group of semi-feral refugee youths who are avid cinephiles, and attend what is claimed to be the last functioning Cinema in the world. The Orpheum Cinema is managed by a mysterious group of Greek exiles, who appear to have immortal status. The narrative is constructed around a series of classic films and structured as a film script.

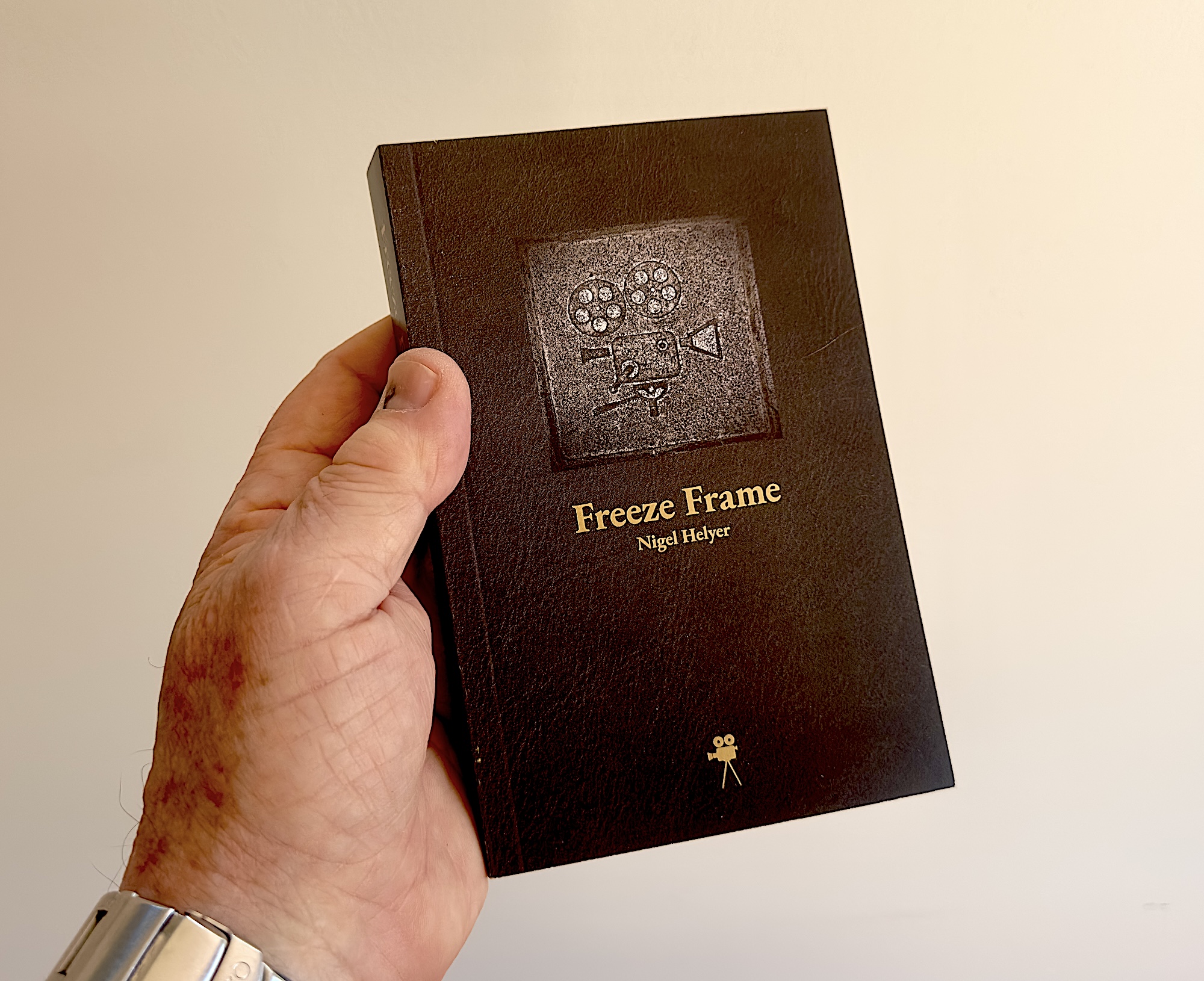

The exhibition is based on a novel of the same name, a labyrinthine 366-page adventure through classic cinema as seen through the eyes of a group of young environmental refugees. To obtain a copy of this unique Artist’s Book email Sonic Objects; Sonic Architecture <sonic at sonicobjects.com> with your name and postal address. The author will send you a PayPal invoice for $35.00 plus postage and packing.

If you are a reader but not financial – then here is a link to an online version.

The Exhibition.

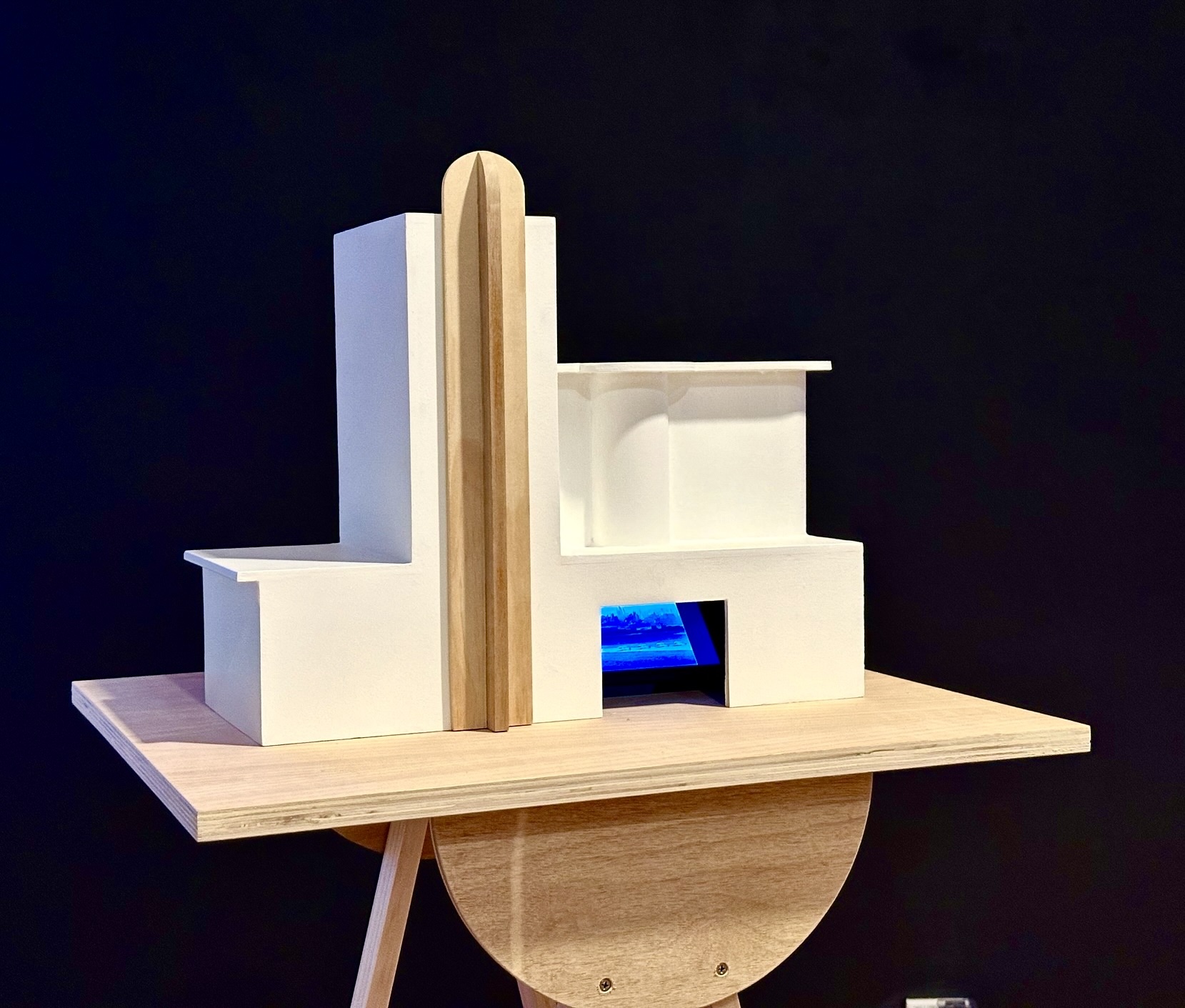

The exhibition at the Macquarie University Gallery (October/November 2024) features a series of twelve scale models that riff on classic cinema architecture. Each cinema contains a miniature digital screen showing a highly compressed version of one of the films that structure the novel. These mini-films are constructed as a series of still images extracted from the original, which are blended in slow dissolves to form a dreamlike precis, overlaid with a voice narrative drawn from the novel.

The Australian Playwright Alana Valentine opened the exhibition with a speech that offered some useful insights into the project and its development, here it is in full.

PERMISSION TO RIFF

A Speech for the Opening of Freeze Frame by Dr Nigel Helyer.

When you are beginning rehearsals for the production of a stage play on a main stage anywhere in the world, the first day of rehearsals almost always goes like this. The performers, creatives and administrative staff gather to welcome the company to the venue. Seated around a table, a script is read, songs are demonstrated and the philosophical and artistic aesthetic of the dance, opera or play is outlined by the director. Then there is a design presentation during which the designer responsible for conceiving and overseeing the building of the set presents their work using a scale model of the theatre in which the work is going to be performed. There is a small, to-scale, seating bank, a small, to-scale, stage area, small, to-scale, curtains and props and set pieces, perhaps a revolve, perhaps a water feature, and usually small, to-scale, human figures placed in the space, some of them costumed according to the costume design concept.

Simon Garfield, the author of Miniature, How Small Things Illuminate the World writes, that ‘As adults, we bring things down to size to understand and appreciate them.’ That, ‘The ability to enhance life by bringing scaled-down order and illumination to an otherwise chaotic world cannot be undervalued. At its simplest, the miniature shows us how to see, learn and appreciate more with less.’

The beginning of any creative venture, particularly the production of an original work for the stage, can certainly be daunting and overwhelming in the best possible way for the playwright. There is a sense of ambition, certainly, but also a continuous struggle to maintain a semblance of seeing the whole at once, of holding in your mind the entirety of the concept as the performers begin to focus minutely and forensically on the details of each and every word. On that first day, for me, when the scale model appears, I always get a sense that by staring at the figures in space, by watching them being moved around design levels, in and out of the entrances and exits and placed in relation to the scale and proportions of the stage I get my very first experience of what I have written. How the words in the mouths of bodies in space will make meaning and play.

So when I first saw these beautiful scale models of imaginary cinemas in the studio of Dr Nigel Helyer, just doors up from where I live in Jervis Bay I was immediately drawn to the pleasure to be had when the human eye is given dominion over an object, a building, in a way that cannot be had in the real world. But as well as miniaturisation to evoke understanding, Nigel’s work invites us to liberate our imaginations to remember, immerse and entertain ourselves with a particular world that he has dreamt into being.

So I invite you to imaginatively come with me now into that studio. Picture yourself moving through a cool climate garden planted and maintained by Nigel’s wife Dr Cecilia Cmielewski. Notice the shocking purple blue of the bulbous hydrangeas, smell the honey-vanilla scent of frangipani, be startled the pops of lemon yellow and lime green on the citrus trees. Move across the grass with me now and enter the doorway of a corrugated shed. At the entrance, silver-grey gravel crunches underfoot, placed there to divert the intermittent flooding that flows past all the houses along our row to the still-flowing creek beyond, echoing with frogs and owls and kookaburras. The air is clean and cold, and once inside the studio, the chill of the large space clarifies the mind.

The models we see in the studio here are, on this first visit, small maquettes made of cardboard. On the walls are tools and books, past projects suspended in plastic sheeting and the floor peppered with shavings and scraps. Go over to the maquettes and peer inside. This is work done by hand with care, with rulers and measures, engaging the brain in detail and creative dexterity. See the artist now, hunched in focus and concentration, the problem solving, the patience of waiting for each glued piece to dry in place. On this first visit I asked Nigel if, for a sculptor those maquettes are like the fabric toile that I might, as a sewer and fabric artist make when creating a new garment. ‘Exactly, he told me. ‘You make the maquette to learn how to incarnate the object as art.’

Weeks pass. The next time we are invited to go into the studio the space is sparsely organised with these full-scale models on plinths, all of them very close to what you see here. Many are now painted white, others are in the process of being painted, and the air that we swirl as we enter is part of their drying process. You notice the blonde wood trim on the buildings, the way they sit on the raw wood rectangular plinths like cats curled expertly in the morning sun. And now the sense of control that responding to miniatures provoked previously has been liberated into an imaginative wonder at the simultaneous unity and diversity of the twelve cinemas on display. Beautiful decorative curves and flourishes, the geometry of smooth surfaces echoing the Art Deco cinemas of the world in California, Paris, Eritrea and Shanghai. Nigel told me ‘These are not real cinemas, they’re a riff. They are from all over the world, but they are very much my version.’

I asked Nigel about the films that he was planning to screen in these miniatures and he explained. ‘I went through the films and I selected images that I felt were both fundamental to the story of the film but also had a visual presence. I put all the images into a Powerpoint, that allows you to control the dissolve rate and dwell time whereas if you do that in a moviemaking software you don’t have long dissolves. Then I exported it as a movie with no sound. Then I went through my text which doesn’t match the narratives of the films because it is written from the perspectives of children misunderstanding what is happening. So for instance in Throne of Blood where the Phantom is winding a thread on a spinning wheel, the children interpret that as people winding film onto spools. Then I took bits of dialogue, not necessarily contiguous dialogue and put them together and then recorded twelve of them into accompanying dialogues of six to eight minutes. If you bend down and look inside the miniatures you will see these films and sound playing on the small screens inside.’

Nigel continued, ‘The Doll’s House in the exhibition is based on a real building in Helsinki in this area of old Russian dachas called Linnunlaulu which means birdsong, it’s forested by a lake. I nearly always stayed in one of these dachas when I was there, in an artist house, they’re like three-story, balconied, gothic-looking houses, but Russian built and in the backyard one of them there’s a dolls house that you could live in, it’s a reduced size and it was probably for the children.’

Soon after those early studio visits, Nigel sent me an early draft of what you have in your hand as the livre de poche of Freeze Frame. Indeed, when Rhonda Davis asked me to open this exhibition her email explained ‘Freeze Frame; cinema and the afterlife is an exhibition based on a novel that explores the relationship between Cinema and the Afterlife. Set in a ‘soft’ post-environmental apocalypse the narrative features a group of semi-feral refugee youths who are avid Cinephiles, attending what is claimed to be, the last functioning Cinema in the world. The Orpheum Cinema is managed by a mysterious group of Greek exiles, who appear to have immortal status. The narrative is constructed around a series of classic films and structured as a film script.’

In Nigel’s own words, ‘ As a thirteen-year-old lad I, along with a couple of friends were once left to kick our heels for the day in central London — we were the crew in a sailing regatta waiting for our helmsman to finish work. Being both wary of getting lost in the capital and having little or no money we decided to visit the cartoon cinema, that in those days was located on the main concourse of Victoria station. However, unlike each Saturday morning, our encounter was not, as we had imagined, with Bugs Bunny or the Invisible Man but with something indescribable and utterly alien. I left the cinema with mixed emotions, no longer an innocent, for I had seen my first film by Jean-Luc Godard and my experience of cinema had been irrevocably changed! ‘

This introduction is followed by an absolutely rapturous premise for a story, the idea of Gods being flooded out of the Underworld by a deluge including this passage which I again must read ‘In the clashing waves struggle the creatures who inhabit the entrance, Penthos who brings grief; Curae anxiety and Nosoi the bearer of diseases. Wildly splashing next to them are Geras the bearer of old age; Phobos the fearful; Limos who spreads hunger and Aporia, need. Thanatos the bringer of death struggles to keep his

head above the foam and Algea who administers agony slips beneath the surface forever. Sleep-casting Hypnos thrashes about next to Gaudia the one of guilty joys; whilst Polemos the warlike is rescuing Eris who oversees discord.’

This is a tale of cinema seen through the eyes of children, of a journeying Poet whose wife is killed by the bite of a serpent, Of King Kong and Moby Dick and Battleship Potemkin and the Wizard of Oz. Of those who inhabit cinemas – the box office staff and projectionist and Janitor. Of the Washington direct current, and the second law of thermodynamics and the Electrotacheoscope. It is the story of portals between two worlds – the world of children and the world of adults, the world of cinema and the realities of life, of the past and how it influences the present, of the imagination and how it suffuses our experience. In it the Greeks hold a private party to contemplate Vampires and the Dalai Lama screens a film by Vertov and conducts a quiz.

It is a dense, complicated tale – as rich as Narnia or Tolkien’s Middle Kingdom but here are the Greeks, the Russians, the French and Swiss and more. And around you are the miniatures that invite you to oversee this world and make sense of it, scaled down to the size of our bodies and the bite-sized, information-bombarded shape of our brains.

Fascination with the miniature and the afterlife has of course surfaced in the form of Egyptian shabti dolls, continued via Lewis Carroll and had its apotheosis in quantum physics. Tonight Nigel invites you to riff on your own childhood experiences of cinema, and architecture and scale models. Walk around and tell your companions, or a stranger, the times you have made or seen or been fascinated by dolls houses, or paper models, or three-dimensional foam puzzles of famous buildings. Or deco theatres that you have visited, or movies that have changed your life. If you are an artist this exhibition is an invitation to understand your own art form through other lenses, for here is the sculptor making architecture about cinema and writing about it in the form of a film script/prose poem. Nigel described it to me as, ‘the nesting’ of one art form within another, within another.

I want to finish with one final observation from Nigel tonight about this work, he says ‘The Wizard of Oz was one of the last pieces I made. And it hadn’t really dawned on me that the structure of Wizard of OZ is echoed by what I have done in Freeze Frame – the characters are both alive in the present, and they are mythological characters, and they are also in the afterlife. They are in three places at once, like Dorothy is in both Kansas and Oz and also in the past and the present at the same time. Other dualities are wrapped up in it too – most especially the small and the large, Ahab and Moby Dick, the sea captain quenching St Elmo’s fire with his bare hand as he makes his crew swear their loyalty to his mission, the sounds competing and interacting with images, the pain and the joy and the way we riff on both.’

‘What is your greatest ambition in life? To become immortal and then die.’ Quotes Nigel from Godard. With three exhibitions currently installed, it’s a mantra that Nigel can quite comfortably claim to be doing his best to fulfil. Sonus Maris, an intriguing exhibition about coastal environments has just closed at the Jervis Bay Maritime Museum, BioSphere/DataSphere opened recently and continues through to March 2025 at the Mawson Gallery in Hobart and here you are, tonight at the opening of Freeze Frame: Cinema and the Afterlife at Macquarie University Art Gallery which I now congratulate Nigel by declaring officially open. Enjoy!

© Alana Valentine, October 2024