BioSonics investigates the morphology of microscopic marine organisms. Installed at the Western Plains Museum and Art Gallery 2008.

A short introduction filmed by Julia Burns.

The rational and the fantastical: the morphology of Nigel Helyer, by Gail Priest.

Despite Star Trek’s propagandist efforts for space as the final frontier, the vast unknown can be found much closer to home in the form of the earth’s oceans. Occupying approximately 79% of the planet it is estimated that only 5% of the watery depths have yet been explored. With the threat of impending environmental disaster the drive to better understand the global ocean has increased and advanced technologies (often similar to those used in space explorations) have enabled access to these previously unreachable zones. However, prior to the technological wizardry of the latter 20th century, scientists had already been exploring the dark, mysterious realms.

An acknowledged inspiration for Nigel Helyer’s work is the German scientist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919). A biologist, he was a strong advocate for Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theories and through his own research identified and named thousands of marine species, as well as developing significant methodologies for the study of biological form and structure known as morphology. What is most influential about Haeckel is that he was also a gifted artist. Before photography and computers scientists were reliant on artistic illustration to communicate their findings and the works of Haeckel, documenting his travels and discoveries, are exquisite.

The scientific and the artistic are generally considered to be oppositional views: science is reliant on fact and rationality, while art often employs flights of fancy beyond what is accepted as reality. Haeckel struggled with this dichotomy and occasionally his artistic inclination dominated his empirical processes with some of his lavishly illustrated findings considered dubious. For example, he employed considerable artistic licence illustrating the ‘similarities’ of the embryonic forms of a range of animals such as the salamander, chicken, cow and human which have since been refuted. However the relationship between art and science is in fact not so incompatible: both practices rely upon experimentation, innovation and even inspiration to achieve their aims.

In Nigel Helyer we see the inverse of Haeckel. Helyer is an artist with a remarkable fluency in the world of the technical and the scientific. Not only does he deftly employ technologies in his work – creating a meaningful, unfetishised usage ensuring that the concepts remain foremost – but he also delves behind standard techniques and devices participating in the very research and development of new technologies. This is evidenced by his involvement in AudioNomad, an ongoing research project (with the University of NSW) into mobile and location-sensitive delivery systems for immersive sound works. AudioNomad was used for the Syren for Port Jackson project (2006) in which a small ferry travelled around Sydney Harbour, the journey mapped via Global Positioning Satellites (GPS), triggering an immersive multispeaker sound journey telling the hidden histories of the foreshores.

The contemporary art science nexus is being extensively interrogated in the field of bio-art, in which artists engage in laboratory practices, using elements of (arguably) living biological material to create artworks. Australia is home to one of the leading facilities, SymbioticA, based at The University of Western Australia. Helyer has been involved with the lab creating his project Host, recently exhibited as part of Ars Electronica, Austria and Transitio_MX02 New Media Arts Exhibition in Mexico City in 2007. Many of Helyer’s works combine a mix of rigour and humour and Host is no exception, using intricate technology to record the electrical activity of the aural nerve of a cricket as it listens to a lecture on the sex life of its own species. The results are represented by an oscilloscope and a sonic interpretation of the data, along with the heavily pixilated image of the original lecture (perhaps a suggestion as to what the cricket sees).

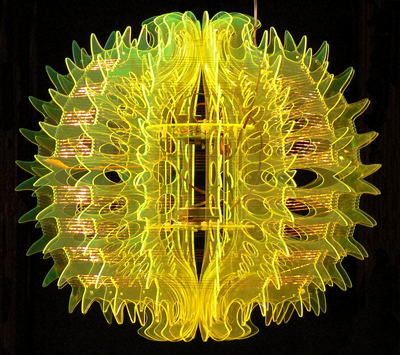

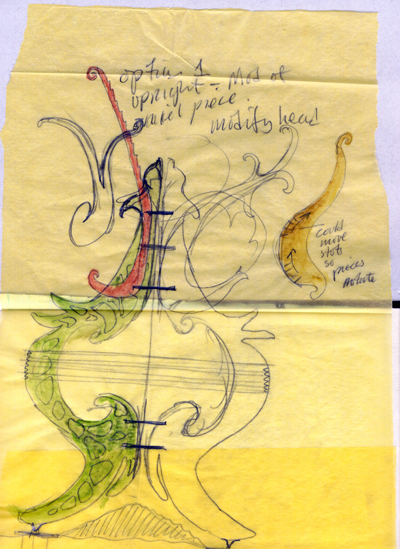

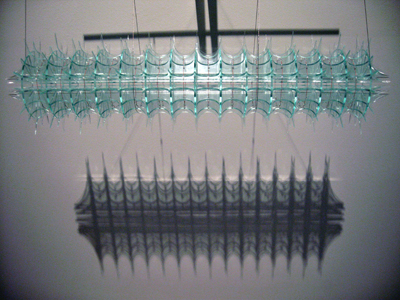

In BioSonics Helyer draws together the preoccupations of these works above: science, living forms, and the sea. Encircling the space is a plethora of exotic sculptural sea creatures. These are extrapolations of life forms inspired by the microscopic wonders of the ocean depths, which have long been the focus of marine biologists, from Haeckel’s era to the present, as they offer insights into the process of evolution itself. Helyer has magnified these creatures, normally invisible to the naked human eye (he studied them via a Scanning Electron Microscope) to illustrate their intricate forms and symmetries.

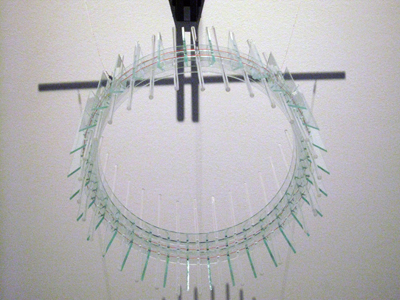

Also drawing upon these microscopic physical forms is the sound sculpture Hydra. The Medusa-like tentacles imply tactility and yet, in this work, are the vehicle for aural communication. Like a menacing sea monster the Hydra has ensnared a strange dwarf ark housing small speakers transmitting lists of fish species – while the fish didn’t need Noah’s conservation services during the great flood, they could do with his help now.

The final work is Transformer in which larval forms embalmed in honey (a gourmet mummification) are encircled by rustic antennae. It’s a kind of techno-shamanistic artefact literally drawing on the electromagnetic energy of the universe to re-animate matter in the form of vibration, creating an inaudible yet undeniably present soundscape.

The accumulative effect of these works is that of a peculiar aquarium in which the microscopic is manifested as massive while the massive (the ark, the electromagnetic universe) becomes diminutive. And of course, it is not unimportant that BioSonics is presented at the Dubbo Regional Gallery, which essentially transports the ocean 400km into the heart of grazing country, alluding to the ‘inland sea’ that Charles Sturt, John Oxley and other explorers endeavoured to discover in the middle of this dry land. Of course, scientists and artists are also explorers: scientists map the mysteries of the inner workings of the universe while artists attempt to map the infinite permutations of the imagination. The world that Nigel Helyer has mapped for us in BioSonics is curious, mythical and fascinating, perhaps more so because it is based in rigorous research and scientific realities.

Gail Priest is a Sydney-based sound artist, curator and writer on sound and media-arts.

Endnotes

National Geographic, U.S. Deep-Sea Expedition Probes Earth’s Final Frontier

For more information go to the national geographic link.

Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur (1904) – Artforms of Nature offering a stunning collection of illustrations is out of print but many plates are viewable at

For more information go to this link.